Who controls what we eat?

The author of a new book on consolidation in the food industry explains the pros and cons of increased M&A activity

By Rachel Cernansky, New Hope Network

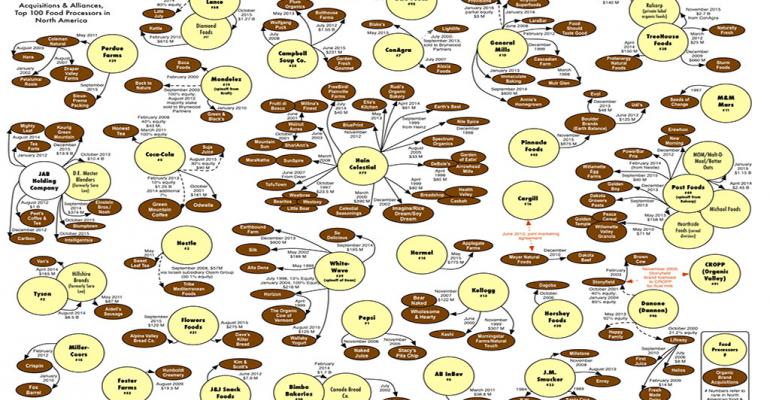

Michigan State University community, food and agriculture professor Phil Howard studies and teaches changes and trends in food systems around the world. His most recent book, Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat?, focuses on how consolidated much of the food industry has become, noting that at almost every key stage of the food system, four firms control at least 40 percent of the market, ultimately allowing them to drive up prices and reduce innovation.

Below is an edited interview with Howard about this trend, some of the impacts it has had on the environment and health and some of the pushback that is also growing in response.

Consolidation has been occurring in the food industry for a long time. Can you talk about the trend encroaching on the natural foods industry in particular?

Phil Howard: There are some pros to the big firms getting involved in the organic industry, particularly those that have maintained a commitment to organic food. They have to comply with the national organic standards, and those standards are constantly changing, but on the production side, for crops, they’ve been pretty stable. The influence these brands may have over standards going forward is concerning—or even if standards don’t change, (companies) source from all over the world and there’s often pressure to reduce the prices they pay farmers. Those are just a few examples of things people are worried about with these changes.

Still, there are actions some of these firms, with their size, can take that would make a big difference. If some of these firms did a better job, for example—particularly the big farms—of sourcing organic seed, then they would see a big shift in the organic industry. But there are loopholes that allow firms to make an effort to source organic seed and if they can’t get it, they can go back to conventional.

The issues you describe seem so massive and thus, in a way, inevitable. Do you see a path for reversing course?

PH: The guy who wrote The Consumer Trap, Michael Dawson, had a great way to answer this. He said the support for the current food system is a mile wide, but an inch deep. Firms are aware of how quickly things can change. That’s why they’re so quick to try to suppress these smaller, independent brands—and if it doesn’t work, they buy them up. And the globe is increasingly networked. When alternatives do pop up and are successful, they grow pretty quickly.

One of the most inspiring things is the seed library movement. Even though several states have tried to shut that down, people are sharing and exchanging seeds, and returning them to a public library.

In the book, you lay out a number of examples of concentrated power—can you point to some industries where this trend is most prominent?

PH: The beer industry is getting close to being just one firm globally. In the U.S., they have some competition. But in beer, you have this market where they’re getting bigger and bigger because that’s the only way to grow. They’re not increasing sales in industrial countries, and they’re facing competition from craft brewers, so they’re trying to increase their power in other ways. They have to cannibalize each other. AB InBev has succeeded in acquiring its second largest competitor in the global beer industry, SABMiller, although it has sold off some brands, particularly in the U.S., in order to comply with antitrust regulations.

The global seed/agricultural chemical industry may become even more concentrated if any of three announced moves are approved by regulators: ChemChina acquiring Syngenta; DuPont and Dow merging; and Bayer acquiring Monsanto. In both of these industries, consumers are likely to see higher prices, less innovation and fewer choices from the remaining firms.

Do you see any silver linings within this trend toward consolidation?

PH: The bad side is these firms are getting bigger, but the good side is more people are becoming aware.

The interesting thing about these firms (is that) they’re interested in power, but because of that they’re able to be pressured by people’s demand that they implement their values. So we’re seeing not just an increase in organic, but changing practices around livestock. There have been shifts in chicken production, for example, as a result of this consumer pressure. Tyson has announced it is phasing out antibiotics commonly used for humans by this year, but pressure came from a key customer, McDonald’s, which previously announced it would be phasing it out by the same date.

There are a lot of signs of hope in that way—people are realizing their power and getting companies to change their practices in more positive ways.

Do you have any other messages for readers in the natural foods business?

PH: I don’t know if it needs to be said, but I talk about how often businesses, when they sell to a larger parent company, will issue a statement about how they’re not selling out—they’re buying in. That’s very common, but it’s also very common for some of the founders of those firms to be disillusioned after a few years, whether it’s because they’re forced out or the values they tried to establish get erased at the bigger firms.

There are some independent companies that refuse to be bought out. I have a list on my site of some of the biggest companies that remain independent. I’ve had people contact me saying, ‘We want to be on your charts.’ Some have recently fallen off—Applegate and So Delicious, for example. But the ones that have stayed have really impressed me that they’ve said no. It would be pretty easy to go under at first when some of the biggest firms are competing against you.

No Comments